arts@sfbg.com

VISUAL ART The new Jasper Johns retrospective currently on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art opens not with his seminal 1955 painting Flag, but with one much less well known from 1956, a painted object titled Canvas. That work is made from a wood stretcher frame and canvas panel turned around to face the wall, the entire back of the thing covered in gray encaustic. Above it on the wall is a quotation from Johns, “I’ve always considered myself a very literal artist.”

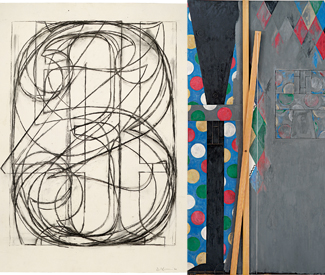

This greeting at the show’s entrance is meant to tell you two things: that you may not be seeing all the most iconic works by one of the world’s most famous living artists, and that you’ll want to take this one slowly, since you’re going to be presented with a methodical review of Johns’ handling of artworks as objects. The central narrative of this excellent show — comprising some 90-plus works, some new and never before exhibited — is Johns’ continuing inquiry into the relationship between what an artwork is as an object and what it depicts.

The first two galleries are dedicated to Johns’ Numbers works, which bookend his nearly 60-year career. The numbers stand in for the other early works, the flag and target paintings that made him an immediate star in the late 1950s and announced the arrival of the post-Abstract Expressionist era. The room is framed by a high key oil painting titled 0 through 9 (pun probably intended), in which a stack of superimposed numerals competes with loud bursts of brushed color. Also in the same room is 1959’s White Numbers, a large relief grid of ordered numerals painted in very thick white encaustic. That impasto grid, texture and all, recurs in a cast bronze wall work from 2005, and a silver sculpture from 2008. Likewise, 0 through 9 is shown also as a charcoal drawing, a lithograph, and a lead relief.

The thing about numbers, of course, is the same about targets or flags. Namely, a painting of a flag is in fact a flag (distinct from how, say, a painting of a tree is not actually a tree). Letting this sink in and acknowledging that Johns is interested in the literal facts (pun intended here, too) of painting and sculpture helps frame how you encounter the rest of the works on display. From start to finish of the show, Johns’ works slowly build in visual and textual intricacy, but tend to circle around this same main refrain.

Johns wants you to understand the complex objects he’s creating, but that doesn’t mean he’ll make it easy. Proceeding by a kind of diffracted metonymy, the various components in Johns’ artworks are both meant to be exactly whatever they are, and also to stand in for a set of other things that also might have been included. This is made explicit in the way Johns mulls over compositions, and transmutes them across media, recasting — sometimes literally — a work in different iterations. Compounding this self-reflexivity, you’ll find statements once proposed as standalone artworks recur later as motifs or referents.

In other hands, this activity might be inexcusably hermetic or academic, but in Johns’ best works the effect is to establish at once both a harmonic resonance between concepts and a continual scrutiny of his own conclusions. For example, in the 1970s-80s Crosshatch paintings, you notice that same numerical grid from 20 years prior, this time reintroduced as the underlying compositional structure of works like Usuyuki (1979-81) or Scent (1973-74). Or, beginning with his 80s Seasons series and continuing to his new Shrinky Dink and Bushbaby images, entire compositions from past works are miniaturized and sampled in new ones, in a highly complex virtualization that juxtaposes metonymy with metaphor. When it works it is astonishing.

It’s axiomatic that an artist will return to established precepts over the course or her career, but few have done so with the explicitness of Johns, who uses his own process as fodder for new deconstructions and assemblages. That the show contains several new works and two new series suggests that Johns, now 82, is not done yet. *

JASPER JOHNS: SEEING WITH THE MIND’S EYE

Through Feb. 3

SFMOMA

151 Third St., SF

ALSO RECOMMENDED:

MARIE BOURGET, KENNETH LO, AND DANIEL SMALL

Marie Bourget’s arabesque paintings take from tile work and ceramics and combine them with translations of Walt Whitman to lovely effect. Through Nov. 22, Johansson Projects, 2300 Telegraph, Oakl; www.johanssonprojects.com

JAMES STERLING PITT

Pitt’s painted wooden sculptures recall both Jonathan Lasker and Richard Tuttle. And that ain’t a bad thing. Through Dec. 8, Eli Ridgway Gallery, 172 Minna, SF; www.eliridgway.com

ROBERT SAGERMAN

Sagerman’s paintings reimagine Georges Seurat’s pointillism as luminous color field paintings. Through Dec. 22, Brian Gross Fine Art, 49 Geary, Fifth Flr., SF; www.briangrossfineart.com